Call for Papers

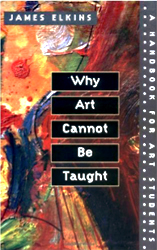

James Elkins, author of the book Why Art Cannot Be Taught states that critiques are "perilously close to non-sense." Charlan Nemeth, academic researcher whose primary research is in group decision making states there are positive effects resulting from stiff criticism. These two views demonstrate the varied attitudes and directions critiques take in schools and departments of art. As instructors of visual art, what can be done to create a beneficial critique?

There are many approaches to critiquing work. Discussing form and the elements of art are necessary to assist in improving technical skills. Examining the artists' intent is necessary. Is it a good idea or a bad idea? What part does the instructor's own work play in the critiquing of others? Sol LeWitt states in his "Sentences: 30. ..The most important (elements) are the most obvious. 32. Banal ideas cannot be rescued by beautiful execution. 33. It is difficult to bungle a good idea." Can these sentences be used as gateways to an informative critique? Are critiques “disordered conversation,” as Elkin states? How is order brought to the critique to make it a constructive and positive experience? What are the important components that make up a good critique? It is informative ideas regarding these questions this session seeks.

James Elkins, author of the book Why Art Cannot Be Taught states that critiques are "perilously close to non-sense." Charlan Nemeth, academic researcher whose primary research is in group decision making states there are positive effects resulting from stiff criticism. These two views demonstrate the varied attitudes and directions critiques take in schools and departments of art. As instructors of visual art, what can be done to create a beneficial critique?

There are many approaches to critiquing work. Discussing form and the elements of art are necessary to assist in improving technical skills. Examining the artists' intent is necessary. Is it a good idea or a bad idea? What part does the instructor's own work play in the critiquing of others? Sol LeWitt states in his "Sentences: 30. ..The most important (elements) are the most obvious. 32. Banal ideas cannot be rescued by beautiful execution. 33. It is difficult to bungle a good idea." Can these sentences be used as gateways to an informative critique? Are critiques “disordered conversation,” as Elkin states? How is order brought to the critique to make it a constructive and positive experience? What are the important components that make up a good critique? It is informative ideas regarding these questions this session seeks.

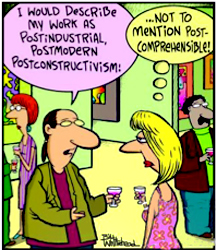

James Elkins’ scathing indictment in Why Art Cannot Be Taught that contemporary art education is a ‘nonsensical’ activity’ bordering on ‘psychosis’ and that group critiques consistently display the dystopian dynamics of power and mind-control like that described in Kafka’s The Trial are, in my experience, as hauntingly accurate as they are profoundly disturbing. This bleak assessment is made even more unsettling by Elkins’ all too predictable refusal to even entertain the possibility that there exists an effective critique format that can help students improve the quality of their work or that there exists an inventive, poetic vocabulary capable of supporting the development of coherent interpersonal critical exchanges.

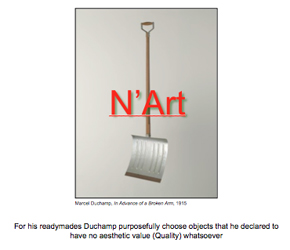

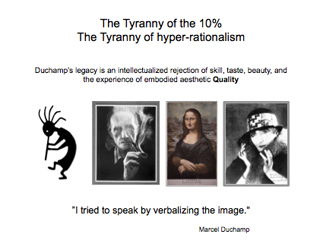

Such aesthetic defeatism suggests to me that Elkins’ cynical surrender is firmly rooted in the widespread theoretical deficiencies that have commandeered contemporary art since the 1960’s. Foremost among these deficiencies is the destabilizing and disheartening re-definition of art that was ushered in with the de-skilling, dematerializing, and anesthetic pronouncements of Marcel Duchamp.

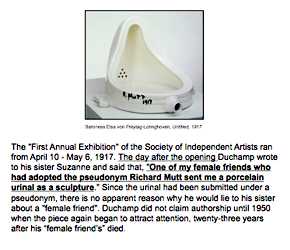

Duchamp has frequently been called the most influential artist of the 20th Century as well as the ‘father of postmodernism’ and anyone familiar with the avalanche of curricula changes that have reshaped art programs around the world over the past thirty years has no reason to question the accuracy of that statement (curiously, Duchamp’s influence is based, in large measure, on his 1960’s claim that he was responsible for the readymade urinal known as “Fountain” when, in fact, we now have now solid evidence that it was actually the work of one Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven).

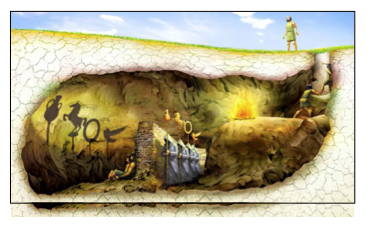

Elkins’ passive surrender to Duchamp’s concept-driven, anesthetic attack on the senses and his apparent willingness to embrace the indeterminacy of postmodern linguistic discourse reflects contemporary culture’s continuing failure to get out from under the hyper-rational premises of logical positivism and materialistic determinism (also known as physicalism) that have for too long dominated and distorted academic discourse in the Arts and Humanities. While both theses distorting premises have ancient roots, namely in Socrates’ denial of the role of sensory perception in human awareness and in his corresponding dismissal of the value of emotion and the visual metaphor in human understanding (remember, Plato expelled visual artists from his utopian society), both philosophical positions encourage blind allegiance to language-dependent, self-reflective, analytical style of knowing that de-couples embodied sensory experience from its real world context by substituting abstract, static re-presentations of fragmented data in its place.

Plato's Allegory of the Cave - physical world as illusion

When these analytical models are used as the bedrock upon which to construct cultural value, what passes as qualitative evaluation of postmodern practice is limited to an appreciation of an artwork’s ability to attack, dilute, and subvert the intellectual, social, moral, and aesthetic assumptions upon which our civilization is based. With this ‘transgression’ of established social values as the standard upon which to rate the value of a work of contemporary cultural practice is it any wonder that Elkins’ concludes that critiques, rather than being tools for stimulating insight and growth, are actually generators of chaos and that educators should forgo the critique entirely and use the time to convince students that their work is uninventive, uninteresting, and mediocre. With this shamefully cynical directive Elkins curiously concludes his book with the observation that art education is teetering on the “edge of incoherence” when nothing in his writing suggests anything less than full-blown incoherence.

When such culturally disruptive, disembodied, and anesthetic methodologies are privileged over innate evaluative criteria that have a long history of engaging embodied meaning through shared perceptual experiences, students are condemned to drift aimlessly in a concept-driven wasteland of unsupportable interpretive vagaries.

This anesthecic trend can certainly be seen in what now constitutes contemporary Art History. Practitioners in this field have abandoned the experience of visual aesthetics so completely in favor of rationalistic theories that Robert Doorly in The Truth About Art observes that 21st Century Art Historians now more closely resemble amateur political scientists, uninformed sociologists, incompetent anthropologists, mediocre philosophers, and arbitrary cultural studies practitioners than Art Historians of the past. By privileging theory over image Contemporary Art History has turned its back on embodied aesthetic experience and embraced the preeminence of linguistic discourse.

Because sensory experience of the phenomenal world is dulled when the senses are intellectualized an alternative can only be found in the long and rich tradition of implicit, metaphoric poetry, music, and visual art that has proven fully capable of inspiring us and propelling us forward toward that which is qualitatively better and toward that which infuses us with joy, fill us with energy, confidence, and a sympathetic sense of our being in and of the world.

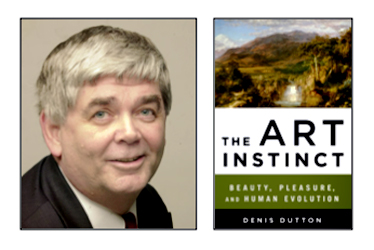

It is as a self-appointed spokesperson for that tradition that I am here today to take issue with Elkins’ position and to offer an alternative model by pro-actively reintroducing a set of innate, intuition-driven sensory-based criteria that can effectively provide a framework for both objective and dynamically fluid qualitative judgments. These judgments are innate and natural and underlie an enduring need in humans traceable back to the Pleistocene era. For 100,000 years our species has dedicated remarkable amounts of energy and resources to make things better, to make things more striking, to make things more resonant, and to make things special in the creation of objects of shared interpersonal meaning. This need to distinguish the better from the good and the best from the better was reformulated during the Renaissance by Vasari. More recently Dennis Dutton in The Art Instinct identifies this innate human need for quality to be a fundamental human characteristic that also serves as the primary mechanism of evolutionary progess.

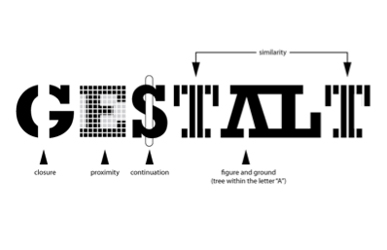

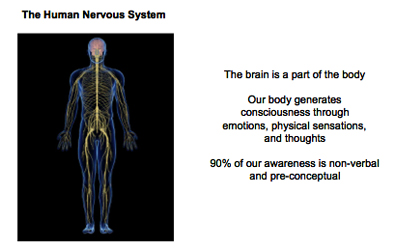

To establish a context in which artwork can be objectively evaluated we must start by acknowledging the root of all human awareness, the human nervous system and its shared embodied sensory experience, as being that from which all qualitative judgments are fundamentally derived. This primacy of perceptual experience is nothing less than the embodied mental awareness that emerges into being when we actively engage with the phenomenal world through our senses and through the inherent perceptual mechanisms identified by Gestalt psychologists. It is these mechanisms that allow us to extract meaning from the chaotic array of complex sensory stimuli in the phenomenal world.

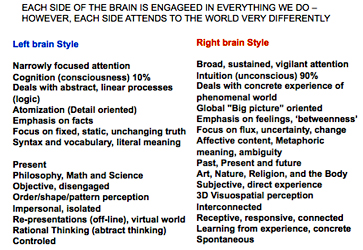

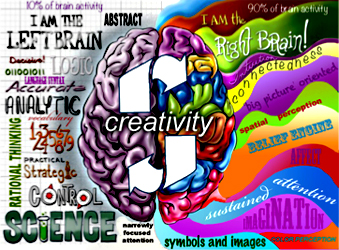

Remarkably, the primacy of perception has also recently been re-affirmed by neuroscientific research studying hemispheric functional differentiation. These studies support the proposition that the bi-cameral structure of the human brain is functionally significant in ways that meaningfully and profoundly shape human lives. The closer one looks at the contrasting styles of our two hemispheres it becomes ever more evident that rational, analytical, and logical thinking are fundamentally ill equipped for understanding the things that give life meaning such as time, gravity, love, honor, courage, justice, self-sacrifice, fortitude, togetherness, friendship, metaphor, music, art, the spiritual impulse, and the affirmation of the ‘isness’ of the natural world. In The Master and His Emissary Iain McGilchrist explains that the differences between the hemispheres is not in what each hemisphere does but it is in how each hemisphere attends to the world. Essentially, we have one brain with two minds – that is to say two processes – one in each hemisphere – two types of attention functioning simultaneously – each process independently generating consciousness and each generating fundamentally opposed realities – with each hemisphere generating distinct sets of sensations, values, and personality– each calling into being individually coherent but stylistically incompatible ways of interacting with the world. One, the left hemisphere, that has been proven to provide narrowly focused, decontextualized, objective, detail oriented attention and one, the right hemisphere, that provides broad, open, alert, sustained, vigilant attention.

It is the right-hemisphere that provides direct and immediate engagement with the world through our bodily senses while the left- hemisphere allows us to distance ourselves from that direct experience by re-presenting our bodily perceptions as rational, cognitive thought. It is theorized that these differences stem from an evolutionary necessity to provide two contrasting but essential ways of engaging with our environment.

Although the left-brain is erroneously labeled the dominant hemisphere because its language processing shapes our conscious idea of self, more than 90% of our brain activity is actually non-verbal. This means that despite the tendency of language to dominate our self-reflective consciousness, the ‘I” inside the head, it is right brain processing, our empathetic intuition, that makes up the majority of who we are. Empathy, intuition, and context ground our sense of self as well as our awareness of everything that lies outside of ourselves. It is this pre-conceptual, pre-verbal encounter that provides the ‘primary consciousness’ of being. In stark contrast the left brain relies entirely on self-reflective knowing, is language dependent and logical, removes experience from its context by constructing abstract, static re-presentations of data, controls its environment with power derived from knowledge comprehended through practical, strategic, efficient, sequenced planning.

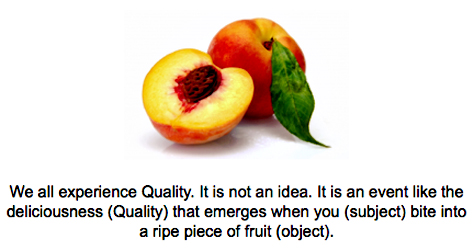

Robert Pirsig’s, in his best selling philosophical inquiry into Quality, Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, first published in 1974, anticipated the power and primacy of embodied perception. He did so with a simple yet powerful illustrative example of what happens when someone sits on a red-hot stove. The empathetic recoil we experience when imagining excruciating pain effectively confirms that sensory engagement with the physical world is not a “vague, woolly-headed, crypto-religious, metaphysical abstraction.” Sensation is not an intellectual representation of an experience. Sensation is not an indecipherable linguistic description of experience. Sensation is pure, embodied experience. It is pure feeling, albeit in the case of the hot stove, an undeniably low quality feeling. Sensation is universally shared experience and it is from these engagements with the phenomenal world that Quality comes into existence. Like the pain of a burn or the sweetness we experience when biting into a ripe fruit, Quality is objectively real and it is shared by all humankind.

Without a doubt, the saddest take-away from Elkins’ book is that a large percentage of art educators working today have lost faith in the implicit, metaphorical, poetic experience of Quality. Gone is the confidence in the inherent value of bodily sensation and in the life affirming experience of sensuous knowing. By denying the fundamental value of bodily sensations art educators forfeit the ability to teach their students the joys of engaging the phenomenal world, of seeing new, of seeing fresh, of looking with care, and of directly experiencing the purity of being. By continuing down Elkins’ dispirited, disembodied path contemporary cultural practicioners are willfully condemning art students to the cheerless gloom of rational, materialist necessity instead of empowering them with the life affirming experience of beauty and excellence, experiences that are known to every one of us through our direct perceptual engagements with nature, our body, our spiritual impuslses, and the fine arts.

As artists and art historians it is our responsibility, as keepers of the flame of empathetic engagement with the phenomenal world, not to allow ourselves to surrender to a mechanistic model of virtual, fragmented, decontextualized re-presentations of consciousness when what promises far greater insight and satisfaction is a fluid, open, infinitely complex, ever changing, endlessly interrelated, relational model capable of shedding light on the fullness with which our brain engages with itself and with all that is outside itself. When it is understood in this way, a critique becomes an opportunity to discover new possibilities and to improve quality while generating energy and confidence.

When approaching a work of art it is crucial to remember that images are more real than words. Visual art is visual poetry and it is with that realization that we can regain a profound appreciation for the soul deepening mystery of the eternal along with the everlasting triumph of the beauty of the natural world. It is with these profound and universally shared insights that we become empowered to lead our students on life-enhancing expeditions into the intuitive world where wonder precedes explanation and where the broad, deep context of being informs the making of art.