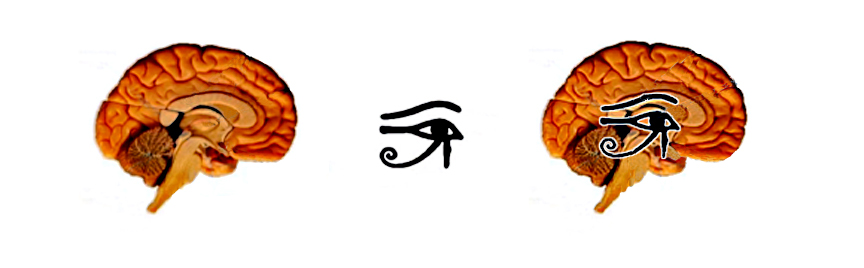

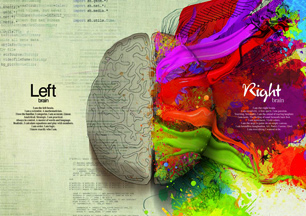

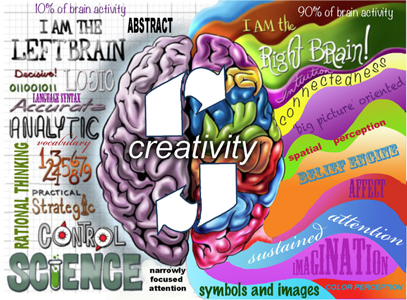

I mention my drawing book because in the first draft of my manuscript I made frequent references to localized brain functionality: identifying the left-brain as the locus of logical data analysis and the right-brain being that of direct perception and intuitive mental processing. I found using the bi-cameral structure of the brain to be a straightforward and effective model for illustrating the profound differences between conceptual and perceptual information processing.

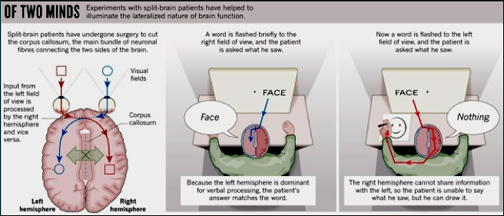

Surprisingly, despite the consistency of Sperry’s findings and despite the fact that he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his groundbreaking split-brain research in 1980, the very next year the previously referenced brain researchers dismissed Sperry’s findings after observing electrical activity throughout the brain during all mental processes. Basing their conclusion solely on their observation of decontextualized electrical brain activity they declared that lateralized brain functionality was no longer a supportable proposition.

As it turns out this was a case of experimental overreach. In the twenty years since I had been made to remove all references to localized bi-cameral functionality from my perceptual drawing book a considerable number of subsequent neurological experiments have shed and are continuing to shed light on the profound differences in localized hemispheric functioning. We now know is that it is not in what each side of the brain does; it is in how each side attends to what it does. I will be returning to this topic later.

About fifteen years after the publication of the first edition of my drawing text a serendipitous conjunction of events renewed my interest in the study of the brain and its relationship to visual perception. The first was discovering the field of Neuroaesthetics while doing research for an art conference panel on the intersection of neuroscience and art. The second was the Federal Government’s announcement in that same year of a $3 billion, BRAIN Initiative whose task was to understand the origins of cognition, perception, and other enigmatic brain activities. I was intrigued by the subject and any hesitation I felt about tackling a topic so far removed from my area of expertise evaporated when I encountered two fascinating, albeit highly speculative, interpretations of classic artworks suggesting a longstanding tradition of artists enamored with the wonder and mystery of the human brain.

Perhaps it was because of my earlier experience of having had my intuitions about lateralized brain functionality so emphatically contradicted by what turned out to be a case of scientific overreach but the more I read about Neuroaesthetics the more uncomfortable I became with its methodology and its findings. Rather than feeling that I had found a tool for providing insights into the mysteries of art and the human mind I began to see Neuroaesthetics as the latest manifestation of a one-hundred-year onslaught of de-humanizing hyper-rational cultural propositions that marginalize intuitive insight and direct, embodied sensory pleasure while privileging language, logical analysis, quantitative measurement, and intellectual abstraction.

While familiarizing myself with Neuroaesthetics, I came across a magazine article in the Skeptical Inquirer magazine titled “The Six Signs of Scientism” by Susan Haack, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy and Law at the University of Miami. This article helped give shape to my concerns about the appropriateness of using decontextualized data analysis to study how individuals respond to a topic as open-ended as the appreciation of art. Scientism, as you may be aware, stems from an over-enthusiastic and uncritically differential attitude toward science, from an unwillingness to see science’s limitations, from believing that science can provide answers beyond its scope, and from a denial of the legitimacy of other modes of inquiry (poetry/art). (2) When I compared the characteristics of scientism with my intuitive misgivings about Neuroaesthetics I concluded that the reductivist underpinnings of Neuroaesthetics set it at odds with the embodied artistic pleasure that has been at the core of the artist impulse since the Pleistocene era (3) and that, if left unchallenged, Neuroaesthetics would continue the century-long devaluation of subjective, unifying, metaphorical aesthetic experience that is the very core of our humanity.

Since its introduction in 2002 Neuroaesthetics has offered scientific legitimacy to the postmodern hyper-rational discourses just as those earlier theoretical models had begun to collapse in on themselves because of their failure to address the embodied emotional and metaphoric character of our consciousness. It is important to keep in mind that Neuroaesthetics is, as is science in general, built upon reductive materialism. In this world-view only the material world is truly real and that all processes and realities observed in the universe can be explained by reducing them down to their most basic components of matter. It is from this reductivist platform that neuroaesthetics feels entitled to conclude, by simply presenting decontextualized blood-flow data, that aesthetic experience “can only be explained by a set of neural correlates”. (4)

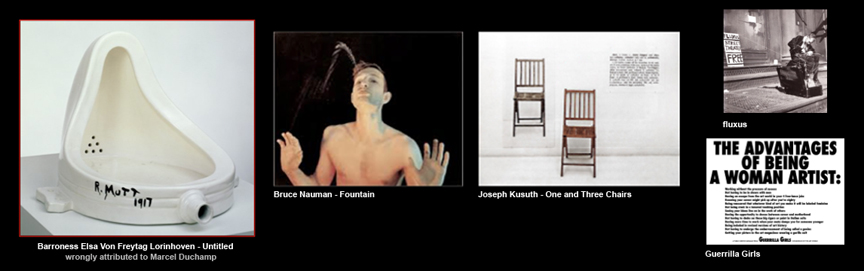

Curiously, the further one drills down into Neuroaesthetics’ research design the more its shortcomings become apparent. For starters, any claim that the subjects in their experiments are being exposed to art requires both a precise and encompassing definition of art and, to date, there is no agreement on a singular definition that is comprehensive enough to address the bewildering complexity of embodied art experience. (5) Without such a definition interpreting localized increases in blood flow as an aesthetic response can only be termed wishful thinking. (6) Secondly, the majority of these experiments are conducted using photographs of artworks rather than the artworks themselves. Curiously, neuroaesthetics gives no explanation as to how such a substitution might affect the aesthetic reactions of the subject. The same problem arises with the content of the artworks used to generate a response. Some of the most publicized neuroaesthetic experiments were conducted using images of female nudes with surprisingly no discussion about how this charged content might skew the results.

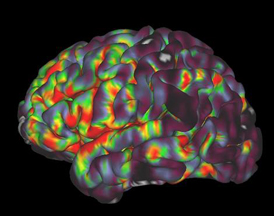

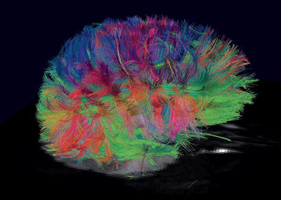

Neuroaesthetics further damages its claim of scientific credibility by failing to address the bewildering anatomical complexity of the human brain. What we don’t know about the human brain dwarfs what we do know. The human brain is the most complex thing we have found in the universe. A typical healthy brain houses 86 billion neurons connected by hundreds of trillions of synapses and each synapse, by itself, is suspected to be more like a microprocessor–with both memory-storage and information-processing elements–than a mere on/off switch. In fact, there is speculation that one synapse may contain on the order of 1,000 molecular-scale switches. (7) That means there might be nearly ninety thousand trillion switches in a human brain.

For a perspective on the scale of the problems posed by this anatomical complexity a recent comparison between the ten-year project of mapping the human genome and the proposed mapping of the human brain suggests that mapping the brain will be one-million times more complicated. Most projections call for it to take at least one hundred years and philosopher David Chalmers has categorized this sorting out of the physical details of the brain’s anatomy as the ‘easy’ problem. ‘Easy’, that is, as in curing cancer or launching a manned flight to Mars. (8) The ‘Hard' problem is understanding how human consciousness emerges from biological, chemical, and electrical processes. And perhaps most humbling in this daunting investigation is that any of the inroads that might be made into the ‘easy' problem is considered highly unlikely to bring a solution to the ‘hard' problem any closer. Keep in mind that there is considerable controversy about whether seeking the mechanisms of consciousness is even an appropriate question for science to ask. Colin McGinn, a British philosopher specializing in the problems of consciousness, has introduced a theory suggesting that our brain is likely to be evolutionarily unequipped “to intuitively grasp why neural information processing observed from the outside should give rise to subjective experience on the inside.”(9)

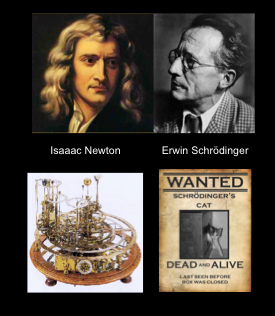

And the problems confronting Neuroaesthetic research get even more daunting. The scientific model underlying Neuroaesthetics is stuck in a theoretical time warp. Its biology is mired in the materialism of Newtonian mechanics even though it has been known for over a century that Newton’s laws don’t apply to micro or macro worlds. Cognition researcher Piero Scaruffi has observed that the more we understand the structure and the fabric of the brain, the less we understand how consciousness can occur at all and speculates on the possibility of an alternative model, that of Quantum mechanics, as a way to explain that which is neither purely material or purely extra-material. (10)

Admittedly, any attempt to explain human consciousness using quantum mechanical processes is currently purely speculative but there are on-going empirical studies that are providing preliminary evidence that living organisms harness functional quantum biology: specifically in photosynthetic light harvesting (quantum superposition) and avian magnetoreception (navigation by sensing the earth’s magnetic field). (11) There are also highly reputable neuroscientists actively researching the possibility of quantum origins of consciousness. Best known of these are Stuart Hameroff, an anesthesiologist from the University of Arizona (12) and mathematical physicist Sir Roger Penrose of Oxford University (13). While the upper hand in this debate is currently said to rest with those opposing quantum consciousness these challenging speculations nonetheless serve to remind us of the profound complexity that is human consciousness.

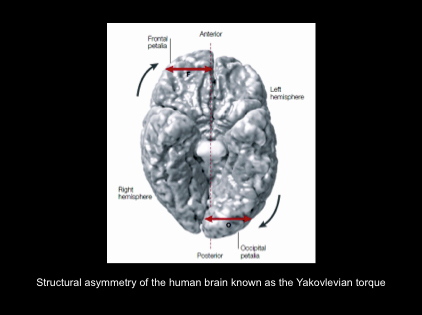

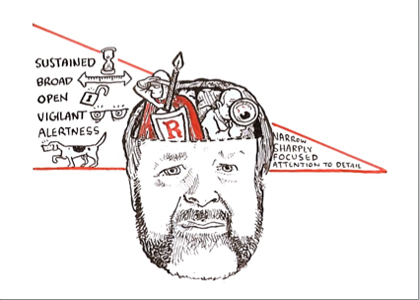

Although Neuroaesthetics falls short in its efforts to provide meaningful insights into the wonder of subjective experience there is, fortunately, an alternate way to apply recent neuroscientific discoveries about the bicameral brain that does shed light on the wonder of embodied sensory experience. It begins with the fact that the anatomy of the two hemispheres of the human brain differs considerably. The right hemisphere is longer, wider, larger, and heavier than the left, has more interconnectivity, and more white matter. The two sides also differ in the number of neurons, the size of neurons, the number of synapses, as well as neurochemical functioning. (14) It is theorized that these differences stem from an evolutionary necessity to provide contrasting ways of connecting with the world – two types of attention functioning simultaneously – presenting two individually coherent but stylistically incompatible ways of interacting with the world. One brain with two halves – each with distinct sets of sensations, values, and personality. One, the left hemisphere, that has been proven to provide narrowly focused, decontextualized, objective, detail oriented attention and one, the right hemisphere, that provides broad, open, alert, sustained, vigilant attention. (15)

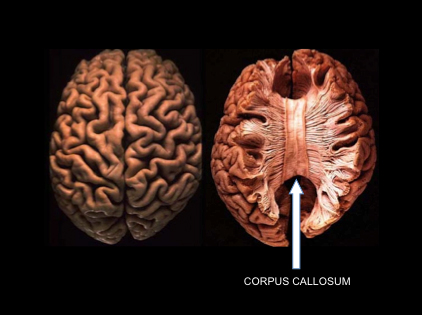

While it has long been known that the two hemispheres are connected by a wide, flat bundle of 800 million neural fibers called the corpus callosum that allows information transfer between hemispheres with radically differing processing styles neuroanatomical research has recently observed that many of these connecting neurons actually perform inhibitory functions thereby slowing down the exchange of information. (16) The inhibitory process is currently presumed to be a way of preserving the integrity of each hemisphere’s contrasting style of processing so as to prevent the confusion that might arise from two oppositional modes of attention.

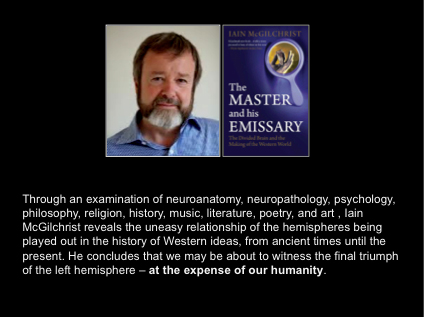

The implications of the hemispheric brain differentiation described above were recently addressed by Iain McGilchrist, a former poetry professor at Oxford and now a practicing psychiatrist and professor of Psychiatry at Oxford. His remarkably engaging, encyclopedic, and innovative book, The Master and His Emissary, uses these contrasting styles of attention as baselines for analyzing cultures throughout Western civilization from pre-Socratic Greece up through the Postmodern period. Before beginning his analysis McGlichrist observes that even though language dominates our conscious idea of self, no less than 90% of our brain awareness is non-verbal. This means that despite the tendency of language to dominate our self-reflective consciousness, the ‘I" inside the head, it is right-brain processing, intuition and empathy, that makes up the majority of who we are. He points out that it is the right-brain relational context that grounds our sense of self and its relation to everything that lies outside of the self. It is this preconscious awareness, this direct reciprocal relationship with the physical world outside our head that forms the ‘primary consciousness’ of being. (17) Or as Descartes should have said, “I feel therefore I am.”

Acknowledging the primacy of perception in no way diminishes the importance of analytical thinking. Even though embodied sensory perception is primary we rely heavily on our left-brain's ability to reprocess our perceptions cognitively so that we can ‘know' them. These rational processes are virtual, fragmented, decontextualized cognitive re-presentations of our direct experience of the phenomenal world. The focused, abstracted, detached attention of the left-brain contributes the necessary distance from the phenomenal world and provides complementary functionality to the alert, flexible, contextual right brain awareness. To be a fully integrated, balanced, satisfied, and creative human being we need to integrate both hemispheric strategies in everything we do. An imbalance in the way we attend to the world compromises our integrity of self. As anyone who has met an individual with catastrophic damage to either hemisphere can attest, such damage brings about pathological disruptions in behavior that markedly compromise the quality of life. For a dramatic book about just how drastically consciousness is transformed when one hemisphere is catastrophically taken offline, I refer you to Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor’s moving first-person account of living through a massive left-hemispheric cerebral hemorrhage titled A Stroke of Insight. (18)

After completing his analysis of the character of all major periods of Western civilization McGilchrist identifies only a handful of historical periods as consistently reflecting traits of balanced functional awareness while diagnosing the overwhelming majority of cultures as disproportionately dependent on modes of attention associated with the left-brain. When McGilchrist’s applies his hemispheric differentiation model to contemporary Western culture he finds its attentional imbalance so severe that it, in his estimation, it reaches the level of behavioral pathology. Such a finding goes a long way in explaining why Neuroaesthetics feels entitled to so clumsily overstep its bounds and displace subjective relational experience with abstract, fragmented data analysis while time-honored traditions of art and the humanities get pilloried by an avalanche of intellectual perspectives that celebrate a world-view whose disembodied, de-contextualized characteristics more closely resemble symptoms of mental illness than one that nurtures the human spirit. We live in a troubled time. As a society, we desperately need to restore balance to the way in which we attend to the world. This is the challenge that Juliette Aristides presented at the 2014 TRAC conference when she knowingly observed that the job of the artist “is not only to identify problems but to repair them” (20)

The balanced bi-cameral model I have described above, a balance that emerges from the unity of logic and emotion, of rationality and empathy, of cognition and intuition, provides just such a restorative strategy. In contrast to the Modern Fallacy (Descartes’ logo-centric world-view in which all that can be known can be known through logic) studying the bi-cameral brain in the context of the physical world clearly reveals that we think with our entire body and that the fundamental truths that provide profound insights onto the meaning of life only reveal themselves through implicit, ambiguous, metaphorical, right-hemispheric pathways. By applying scientific data about the bi-cameral styles of awareness as a diagnostic tool for understanding wide-ranging cultural characteristics, McGilchrist reminds us that the antidote to the pathological imbalance in both individuals and in society is rooted in acknowledging the primacy of perception. From what I have read of the previous years' presentations from the TRAC conference if McGilchrist were here with us today, he would find himself joyfully preaching to the choir. After all, by resisting popular cultural trends and art world celebrity the artists assembled at The Representational Art Conference have chosen to dedicate themselves to the open, fluid, infinitely complex, ever-changing, endlessly interrelated metaphorical pursuit that is balanced mind/body awareness. This balance enables representational artists to embrace an active, perceptive manner of sight that challenges both ourselves and our audience to look deliberately, to look intensely, to seek meaning in experience, and to pursue a state of complete awareness of the physical world of which we are a part. Such active engagement with the physical world is “seeing” in the fullest sense of that word. Skillful, hands-on studio practice serves as a uniquely effective bridge to a world much broader and deeper than oneself, to the ineffable world of being, into the "is-ness” of the material world. Skilled artists embrace the intuitive world and feel most comfortable communicating through their senses and in so doing acknowledge the authority of the sacred world outside their heads. This is what we mean when we speak of sincerity, authenticity, and creativity in art and it is what we mean when we speak of the primacy of perception

(1) David Wolman, The split brain: The tale of two halves, nature.com, http://www.nature.com/news/the-split-brain-a-tale-of-two-halves-1.10213

(2) Susan Haack, "Six Signs of Scientism Part 1", Skeptical Inquirer, Vol. 37 No. 6, (November/December 2013), 41

(3) Dutton, Denis, The Art Instinct, Bloomsbury Press (2010), 142

(4) Semir Zeki, Statement on Neuroesthetics, (http://www.neuroesthetics.org/statement-on-neuroesthetics.php)

(5) Noe, Alva, "Art and the Limits of Neuroscience", The New York Times: Opinator, http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/04/art-and-the-limits-of-neuroscience/

(6) Noe, Alva, "How Art Reveals the Limits of Neuroscience", The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Chronicle Review, September 8, 2015

(7) Moore, Elizabeth Armstrong, Human brain has more switches than all computers on Earth, http://news.cnet.com/8301-27083_3-20023112-247.html

(8) Oliver Burkman, "Why can’t the world’s greatest minds solve the mystery of consciousness?", The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jan/21/-sp-why-cant-worlds-greatest-minds-solve-mystery-consciousness

(9) Pinker, Steven, "The Brain: The Mystery of Consciousness", Time, Jan. 29, 2007, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1580394,00.html

(10) Piero Scaruffi, Quantum Consciousness, http://www.scaruffi.com/science/qc.html

(11) Neill Lambert, Yueh-Nan Chen, Yuan-ChungCheng, Che-Ming Li, Guang-Yin Chen, & Franco Nori, Quantum Biology, Nature/Physics, http://www.nature.com/nphys/journal/v9/n1/full/nphys2474.html#close

(12) Stuart Hameroff, Quantum Consciousness, http://.quantumconsciousness.org

(13) Penrose Roger Penrose: The Quantum Nature of Consciousness (video lecture), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3WXTX0IUaOg

(14) Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary (Yale University Press, New Haven, CN, 2009), 33

(15) McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, 3

(16) McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, 17

(17) McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, 176

(18) Jill Bolte Taylor, A Stroke of Insight, (Plume, New York, 2006)

(19) McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary, 428

(20) Juliette Aristides, "The Enduring Value of Art", in Kitsch and Beauty, ed. Michael Pearce, (CLU Press, 2014), 245