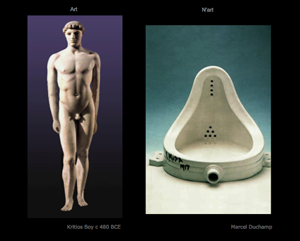

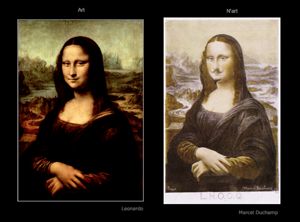

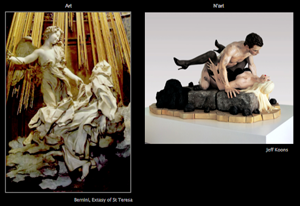

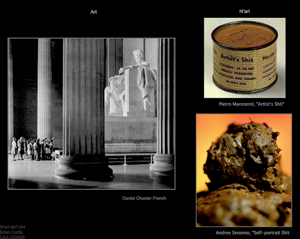

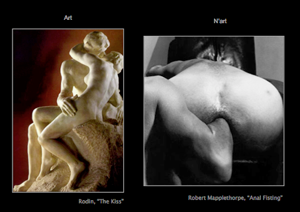

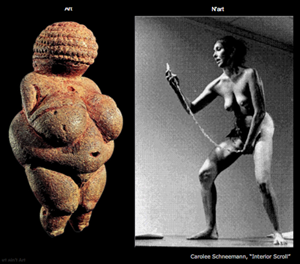

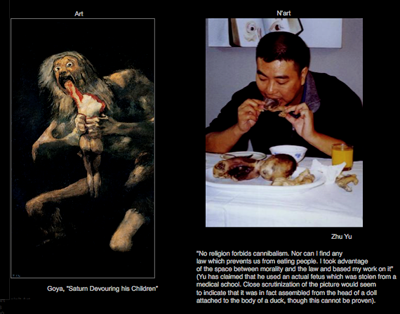

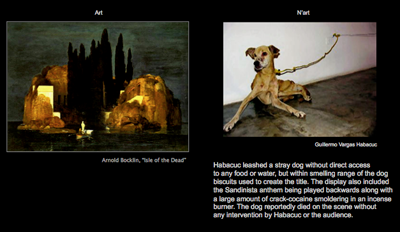

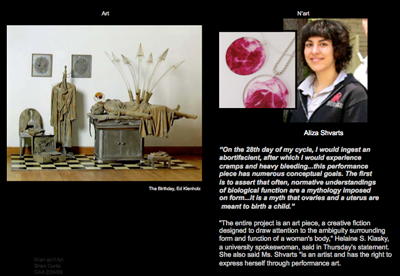

University and college art programs once nurtured visual sensitivity, talent, craftsmanship, and creativity. Recently, however, these goals have been displaced - and are increasingly being replaced - by the de-skilling and dematerializing promotion of a conceptually oriented approach referred to as contemporary cultural practice or postmodern art. For reasons that I hope will become clear, I call it N'art.

The relatively recent pedagogical switch from skill based instruction in specific media to a curriculum rooted in conceptualism, pluralism, deconstruction, and the privileging of “new” media follows shifts in the international art market. If you believe that the art market is the appropriate arbiter of what is important in our visual art culture, then you are likely satisfied with the current state of college art curricula. If, however, you are among those who believe, as I will attempt to demonstrate today, that the theoretical underpinnings of contemporary cultural practice are inherently unsuitable as a framework upon which to construct a meaningful art curriculum, it behooves you to identify and implement a more life-affirming approach to teaching of art. But before addressing alternatives to the current situation, let us take a look at the pedagogical model that currently informs art programs at American colleges and universities.

For starters, the conceptual nature of the postmodern pedagogy that privilidges content over form, severs contemporary cultural practice from its long-standing artistic roots. Secondly, in promoting pluralism, postmodernism inserts a constantly changing, ever-broadening definition of art that subverts the tradition of a singular best and belittles qualitative standards, individual creativity, originality, intellectual discipline and structured learning. And thirdly, constructing a curriculum around a deconstructive linguistic discourse can’t help but establish a profound self-contradiction in as much as once deconstruction is institutionalized as a foundational pedagogical principle it immediately becomes reconciled with the power structure that it claims to be attacking. Oops!

Despite the unavoidable contradictions inherent in a postmodern art curriculum, school administrators are nonetheless predisposed to embrace this radical curricular model for any number of reasons, not the least of which is that academic administrators are, by nature, more comfortable with linguistic discourses than they are with the manufacture and evaluation of a hand made cultural products whose value is intuitively determined by an intuitive experience of visual quality. For programs (like art) that receive little or no validation in terms of external research support, administrators are under increasing pressure to support curricula initiatives that can be marketed as avante-garde or bleeding-edge. When one takes into account the fact that institutional rankings and notoriety in the visual arts today are more easily achieved by tailoring programs toward nonhierarchical, experimental, contextualized, interdisciplinary, integrative, theory dependent, pluralistic, multicultural, issue oriented, community sensitive, multivocal, technologically oriented, intermedia cultural practice that may or may not include a visual component, the motivation behind the institutional strategy becomes clear. To give an example from my home institution, this past December our Dean announced a $5,000 summer stipend for faculty interested in designing courses that break new ground, move outside the existing curriculum, or transform a current departmental offering into an interdisciplinary program. So important did the Dean consider this recent initiative that he had the proposals sent directly to his office for approval, thus circumventing the customary review by both departmental and college curriculum committees who might be so retardaire as to raise concerns about how these proposed courses fit into the existing course offerings. As I imagine you have experienced at you home institution, the question in academia is no longer “is it a well-considered program of appropriately sequenced and structured courses with clear and precise outcomes,” the question now is only, “does it suggest innovative definitions of what constitutes a basic education in art.”

If you are of the opinion that I am being heavy handed and unfair in my characterization of postmodern pedagogical practice I suggest that you read Dr. Jodi Kushins article, Brave New Basics in FATE in Review for 2008 – 2009. In this article Dr. Kushins summarizes her doctoral dissertation that focused on institutional portraits of introductory programs at two highly ranked studio art schools, Carnegie Mellon and The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She begins her article with the appropriate value-free definition of innovation as any departure from traditional practice but quickly switches, without explanation, to an unchallenged suggestion that innovative programs are by nature more productive and engaging as well as artistically and intellectually motivating. The only rationales she offers for her support of the “innovative” curricula at these two programs was that the students liked them and that they differed from what had been taught in the past. Dr. Kushins seemingly gets caught in the same prejudice that ensnarls most college administrators, namely, that anything new is inherently better than what it is replacing.

The rejection of tradition becomes so pervasive in this article that Dr. Kushins gradually acknowledges the need to “create a new language’” with which to “reconstitute the grounds on which the cultural and educational debates are to be waged.” Gone is the term ‘foundations,’ since it implies a hierarchical order of principles and media with which students must become familiar. In its place Kushins supports substituting the word ‘core’ as a way of recognizing that there is no longer a recognized skill set or media discipline that is important in the training of artists. This open-ended attitude about the nature and objectives of undergraduate introductory coursework was summed up in a quote from a veteran faculty of the introductory curriculum who states “we don’t pretend that we are preparing finished painters or finished anything.” This freely admitted lack of intentionality certainly provides an explanation as to why James Elkins, who works at one of the two profiled institutions, would write a book titled Why Art Cannot be Taught. While I am not a believer that art cannot be taught I now realize that Elkins works with faculty who have little or no intention of even trying to do so.

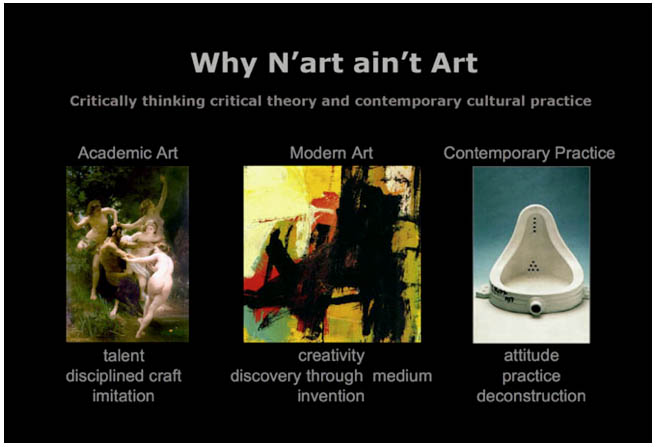

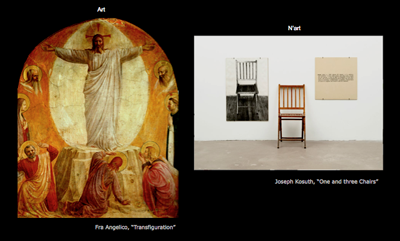

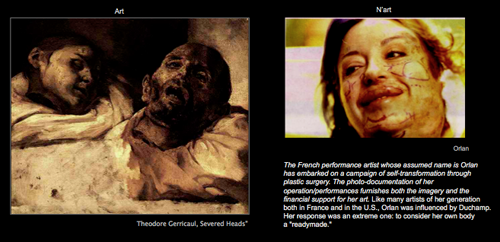

In place of actual training we are told that students are now being exposed to conceptually driven artmaking practices using ‘new media’ (she specifically mentions sewing and baking) that help students develop critical awareness of the relationships between concepts and context. Acknowledging that these curricula are continuing the legacy of Marcel Duchamp and his denouncement of craft, his assault on good taste and his aggressive rejection of “retinal” art, Kushins goes on to quote a faculty member from the Art Institute of Chicago who refers to these innovative curriculum as “deprograming,” where the incoming students are “forced” to let go of their previous notions about art making.” Instructor attitudes like these amount to nothing short of an indoctrination into the belief that to be innovative demands a wholesale rejection of visual aesthetics and craftsmanship.

For those of us who revere the western intellectual tradition, a particularly troubling development in the recent evolution of the postmodern art curriculum is the sudden increase in the number of art courses and/or course modules that claim to be teaching critical thinking when what is actually being taught is second-hand, warmed-over critical theory. If anyone doubts how pervasive this development is and how critical theory is presented as critical thinking, I again refer you to the latest issue of FATE in Review, this time pointing you toward the twenty-three page summary of last summers Integrative Teaching Think Tank titled Putting Theory to Work: Building a Foundations Program for the 21st Century.

Let me clarify the two issues I have mentioned. Critical theory is a collection of radical theoretical perspectives that have replaced the idea that facts and evidence matter with the idea that everything boils down to subjective interest and "local community" perspectives. As such, critical theory is intended to challenge the established order. Unfortunately, such a position is a destructive form of anti-intellectualism that renders the Western rational tradition irrelevant.

Critical thinking, on the other hand, is the process of applying the logic and thoroughness of the scientific method to our everyday experience. Critical thinking is not a natural process, it is often counter-intuitive, and learning it has been likened, in degree of difficulty, to learning a foreign language. It should be taught, but only by trained professionals. Studio art faculty are not the appropriate instructors to impart this challenging skill-set given that the overwhelming majority of studio faculty have little or no training in the rigors of critical thinking. Without specialized training in critical thinking and without the peer review of their content and methods, studio faculty are prone to disseminate misinformation, personal biases, inadvertent indoctrination, and simplistic analyses in the guise of critical thinking. Teaching critical theory under the banner of critical thinking is not simply deconstructive, it is dishonest and destructive.

While I clearly understand why a contemporary art department would want to cloak its progressively fragmented and disorganized curriculum with the liberal arts gravitas associated with the rigor of critical thinking, this initiative is intellectually flawed. Were art faculty truly committed to critical thinking they would begin by actively dispelling the illusion that postmodernism's rejection of reason and intellectual certainty is compatible with critical thinking. We would also expect disclosure, analysis, and discussion of the anti-cultural and de-civilizing implications of the foundational ideas of those who contributed to the deconstructive postmodern world-view? Studio faculty committed to critical thinking would make it clear to their students that in adopting postmodern cultural practice they effectively reject the principles of the Enlightenment in as much as postmodernism discards belief in objective truth, optimism about human progress, egalitarianism, the validity of scientific method as a means to arrive at truth (logic), the universality of reason, the importance of individuality, not to mention the overarching political ideals underlying the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States? Oh, those pesky metanarratives!

Unfortunately, it is just this sort of metatwaddle and not critical thinking that is providing the rationale for postmodern art pedagogy. At my university it is not uncommon for students embracing contemporary practice to be able to recite a litany of the names of postmodern theorists; Adorno, Derrida, Foucault, Boudrilard, Lacan, Lyotard, to name just a few. These students are also familiar with theoretical fragments of these theorists’ contributions to postmodern theory. However, rarely are these students asked to consider dissenting opinions such as those addressed in what is known as the Sokol affair. Alan Sokol, as you might remember, was a physicist from NYU who, in 1996, decided to reclaim the legitimacy of the Western rational tradition from those prone to theorybabble. To make his point he wrote a parody of a postmodern article and submitted it to the then prominent postmodern journal Social Text. Unaware that it was a parody the journal published it. Ooops, their bad.

Sokol's experience is not unique. In 2006, consistently frustrated over the prepoderance of postmodern-leaning panels at national art conferences, I, too, adopted this approach and wrote a parody of a postmodern paper titled, nonsensically, Chromatic Vacancy and the Collapse of Visual Curatorial Color Coding and submitted it to a SECAA panel at the Nashville conference that had posted what I had considered to be a egregiously indecipherable call for papers. Sadly, my submission was not only accepted, it drew enthusiastic praise from the panel chair. The chairs effusive response made me feel like I was clubbing baby seals so I wrote to tell the panel chair that a scheduling conflict prohibited me from participating with his panel. He wrote back that he was very disappointed and that I owed him a six-pack of beer. I didn't buy him the beer but I did sit in the back of the audience for part of this panel and can tell you that the participants all appeared to take themselves very seriously.

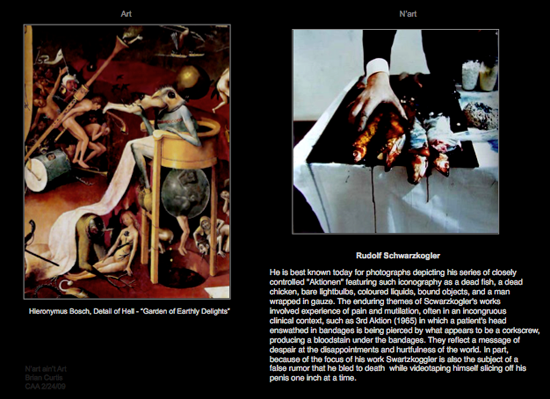

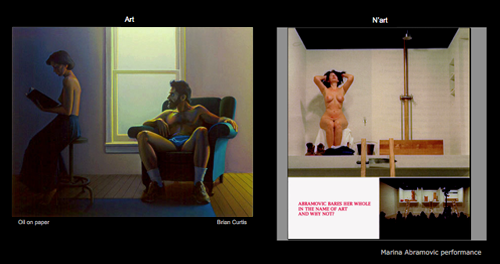

Unrelenting, de-civilizing sentiments have pervaded the art, artist statements, art manifestos, and art criticism for the last 35 year and this spirit lives on every time the adjective transgressive is used to dispense praise upon a contemporary cultural practice. Transgressive means to violate a law, a moral code, to offend. The frequency of use for this postmodern value criteria has been characterized by critic James Gardner as the “donutization of the art world” where one's artistic relevance is a function of one's distance from a center that is defined as being occupied by the “pale, capitalistic, patriarchal, penis people. Under this model, postmodern cultural practitioners are revered as transformative revolutionaries whose role it is to attack, dilute, and subvert the bedrock of cultural traditions: the intellectual, social, moral, and aesthetic assumptions upon which our civilization is based. Such sentiments presuppose that the straight, white male is unredeemably ignorant, unrepentantly selfish, inherently complacent, incurably bellicose, and deserving of every possible abuse and insult. In reality, what we are left with is a series of oversimplified sophomoric attacks on a stereotypical scapegoat. The conceptual “one-liners” that make up so much of contemporary cultural practice remind me that, “There's no cliché in art quite as popular as the cliché of challenging cherished clichés.”

I find it fascinating that no matter where I travel the student work I see put forward as contemporary cultural practice, postmodern art, or N’art all looks the same. It looks like it was made with cookie-cutter recipes, like those that can be found in the entertaining spoof, 100 Rules for Success in the Contemprary Art World by Earl Bronstein of Ft. Lauderdale, Florida that he once made available free from his site. Here are some of his 100 helpful guidelines:

More is Better – Exhibit hundreds, or better yet, thousands of objects.

Use Dead animals.

Video is big, big, big.

The longer it takes, the more mundane the task, the more common place the object used, the more monotonous the activity, the more it is adored by curators and art critics.

Tie up or cover up anything and everything.

Take a digital photograph.

Try performance art – making a fool of your self is good - as is nudity.

It is good to be gay.

Things that go bang, twirl, or fill with air are irrestible.

Exhibit objects that hang from the ceiling.

Use excrement in your art.

Use dirty words in your art.

Build a boat out of wood.

Sew and ye shall reap and ye shall exhibit

Curiously, when I share Dr. Bronstein’s recommendations with graduate students at my home institution they react with strong condemnation for this author’s lack of understanding of the importance of transgressive cultural production. In my opinion, they are just embarrassed that Mr. Bronstein has drawn attention on the pretentious wizzard “behind the curtain.”

Despite the popularity of radical theoretical perspectives in the 21st century postmodern academy, there are some among us who still look at art issues from a modernist, enlightenment, life-affirming perspective and in that spirit let me close with this exhortation, “Teach your students to care, Encourage them to feel and to touch. Expose them to the joy and satisfaction that comes from being constructive rather than deconstructive. Provide them the tools to meaningfully respond to the things in their experience that are beautiful and alive. Instruct them on how to draw, paint, sculpt, model, print, and weave before exiling them to the anti-art wasteland.

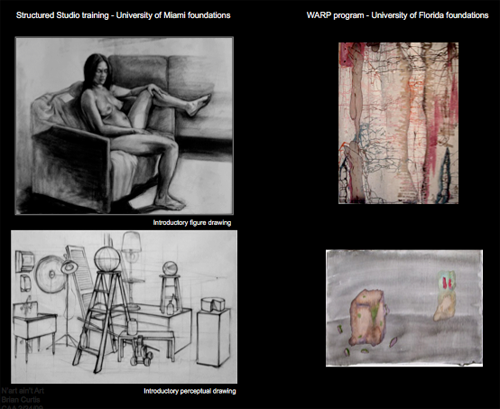

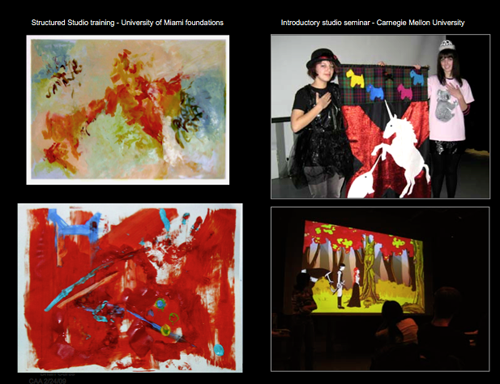

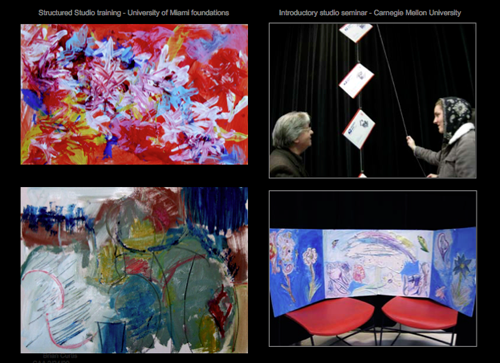

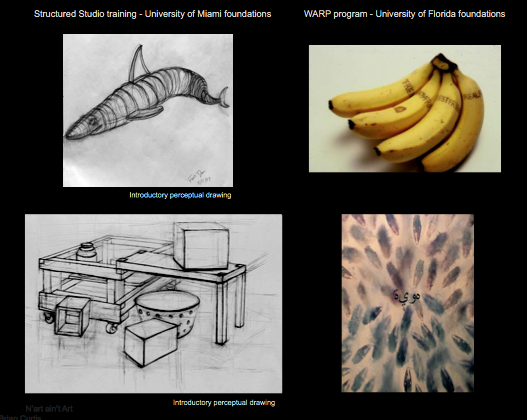

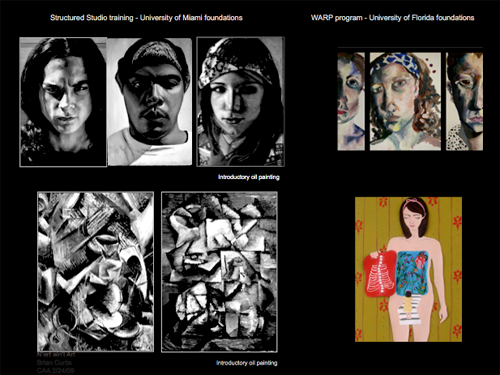

Structured, skill-based studio training vs. conceptually based foundations