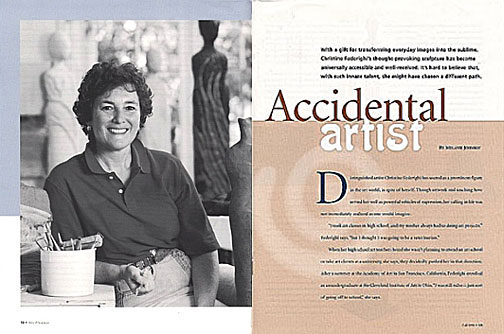

CHRISTINE FEDERIGHI

Accidental Artist

BY MELANIE JOHNSON

Distinguished artist Christine Federighi has soared as a prominent figure in the art world, in spite of herself. Though artwork and teaching have served her well as powerful vehicles of expression, her calling in life was not immediately realized as one would imagine.

"I took art classes in high school, send my mother always had us doing art projects,'

Federighi says , but I thought I was going to be a veterinarian."

When her high school art teachers heard she wasn't planning to attend an art school or take art classes at a university, she says, they decidedly pushed her in that direction. After a summer at the Academy of Art in San Francisco, California, Federighi enrolled as an undergraduate at the Cleveland Institute of Art in Ohio." I was still naive—just sort of going off to school,' she says.

By her junior year a spark had been ignited, and she became serious about her work. "My brain just all of a sudden clicked in on all the things I had to do to be better,' she says. Her undergraduate instructor and mentor, Joe Zeller, laid the foundation on which Federighi would begin to build." He was strict and tough,' she says." He saw that I was hardworking but needed guidance and structure"

Afterwards Federighi attended Alfred University— the Oxford of the ceramics world. A prestigious science and technology school in Alfred, New York, Alfred's courses range from ceramic engineering to studio art. After receiving a Master of Fine Arts degree, she joined the University of Miami as a faculty member in 1974.

assumed I was a hard technical whiz, and they were going to glean all of this technological information from me."

Before joining the University, Federighi was producing a pell-mell of mixed pieces while in Cleveland. When Zeller came along, he guided her toward functional and studio pottery. At Alfred, she was still creating functional pottery but was pursuing other avenues as well.

"My thesis show had blown-glass pieces, sculpture, and functional ware," she says. "Mv advisors weren't too happy about it, but I just couldn't decide which to focus on.' Federighi thought she might even be a glass blower for awhile after spending a summer at the Pilchuk, a glass blowing center in Washington.

But when she came to Miami, her work shifted again. She left her bread-and-butter functional ware—which she sold at shows and galleries to put herself through school—to direct her energy toward more sculptural creations. She began to hit her stride when she abandoned utility and started thinking about the poetics of the pot.

Her travels to the Southwest led Federighi to carry her art to another level, a narrative step, by making pots with landscapes suggesting the region. Inspired by American Indian and tribal art, she adopted their decorative use of symbolism. She imitated theirs for awhile before developing her own. Next she moved on to creating little dioramas with figures in them, which over time grew larger, more human in scale.

The turning point in her career came in 1979, when she landed a show for her latest body of work. Visitors to the exhibit were surrounded by whimsical folk art animals and figures arranged as an environment. Many were life-size and narrative, looking as though they just leapt out of Aesop's fables.

"All the pieces sold. The Miami Herald gave me a really terrific review,' Federighi says. "People still to this day talk about those pieces."

For Federighi, her work is a diary. "The changes that mv work has gone through all relate to my life,' she says. "In many ways, sculpture is a journey" First there's its own physical transformation through shaping, hardening, drying out, firing, and coloring its surface, she explains. Then there's her own. "I worked in a longtime theme of horse and rider,' she says. "Owning a horse was definitely a journey."

When she gave up horseback riding, the human figure became important to Federighi. She streamlined a faceless, limbless shape and carved different images onto its archaic form. When she began vacationing in Colorado, richly painted rocky mountain and river landscapes engulfed her human-like sculptures.

"I was developing a personal symbolism with western images," she says. "I was almost denying the fact that I was living in Florida."

Federighi finally embraced this reality when she was commissioned to develop a piece for a library at Florida International University. Their only request was that it depict its site, a tropical setting on an inland waterway. The different stylized leaf forms she created would become a recurring theme wrapping her columnar figures, paying homage to Florida for its positive impact on her growth.

But art continued to imitate life. While she was building a house in Colorado, Federighi grew intrigued by the process of divining and drilling for a well. She adapted the spiral of the drills into metal rods encircling her figures. For her, the spirals are also an infinity symbol for eternal life. During her home's construction phase in 1993, she dappled her pieces with broken up house structures.

Federighi's trademark human narrative brings all her personal visions together—the Florida plant life, houses, stairs, the Colorado landscape, and water.

Playing monopoly as a child led her to choose its simplistic shape for the house, one of her main symbols. "The house is a feminine symbol, and I am a homebody,' Federighi says. "I also realized I had three places I called home. California was my birthplace, the Southwest is my spirit home, and Florida's my residence."

The University of Miami is another home to Federighi, who first came to the University when she was 25 years old. "That was 24 years ego,' she says incredulously." I really grew up here." By reorganizing and expanding the curriculum, Federighi has created an outstanding ceramics program as evidenced through highly praised student exhibitions. She and her students also formed the Potter's Guild, which holds annual sales to raise funds for visiting artists and new equipment.

In looking back, she recalls the laborious efforts behind rebuilding the ceramics studio for the University." More help would have been nice, but I think it was part of my growing process,' she says. Since then, its growth has been tremendous, including a sturdy roof over new kilns, nice equipment for the students, and a part-time technician who helps out.

She credits the University for helping her reach her full potential as an artist. "Because we're a research

university, there's a certain amount of freedom to do my work," she says. "I always thought I was going to go back to California, but if I had, my work probably wouldn't have been the way it is."

Though she likes to have time to do her work, she also enjoys teaching. "I definitely have to do both,' Federighi says. "Students' feedback can surprise you; it keeps me alive."

One unexpected turn in Federighi's life was not so welcome. In 1995, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Told to "take it easy" by her doctors, she reluctantly slowed down. She read books on healing and learned about visualization, good cells, killer cells, and T cells. For every day she had cancer, she sculpted a softball-sized "good cell" as her activity or meditation, pouring positive energy into it. When her treatment first began, she presented each of her doctors with a sphere, onto which she carved her personal symbols. Nurses and friends all received an original ball when she beat cancer and left the hospital.

Now the cancer is back, this time in her bones. After treatment she describes as "heavy duty"— chemotherapy radiation and bone marrow transplants—she's back to work but not focusing on the disease.

"For many artists it's such a profound thing to go through an illness, they put it into a tougher statement," Federighi says. "But I didn't want to relive the surgery and treatment." As the story leaks out, consumer interest in the spheres is growing. "It's still kind of hard to sell them, because they have this other meaning,' Federighi says. "They're like talismans or good luck charms."

As this year's invited Florida artist in August at the Lowe Art Museum, Federighi recently completed 18 pieces for her installation. Spheres of all different sizes are premiering in her collection. Next she'll create large bronze spheres for the new Biscayne Nature Center on Key Biscayne. Slow down?

"Moving the clay is calming; it's a time to focus,'she says."It's something that I always do. When I'm not doing it, I feel off balance."

Melanie Johnson (B.A. '95) is nn editor in the Department of Publications and a graduate of the Departmentt of English in the College of Arts and Sciences. Photography by John Zillioux.